Shock: Assess and Manage

Gregory A. Schmidt, MD

Clinical Professor

Pulmonary – Critical Care Medicine

July 2020

As chiefs we highly recommend watching the video for Dr. Schmidt’s lecture as he has numerous dynamic ultrasound images with clinical context. We have highlighted the lecture below and provided various other resources to build your knowledge of shock.

OBJECTIVES

-

Learn to ask physiologic questions

-

Is the cardiac output low?

-

Is the heart empty?

-

Is there pump dysfunction?

-

-

Recognize the causes of shock

-

Know an approach to vasoactive drug infusion (earlier may be better)

Shock Definition:

-

Circulatory failure causing tissue hypoxia

-

Usually MAP is low (blood pressure is a surrogate for blood flow)

-

Usually global oxygen transport is low

-

Microvascular dysfunction may play a role

-

-

Leading to dysfunction:

-

AKI, Encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, respiratory failure

-

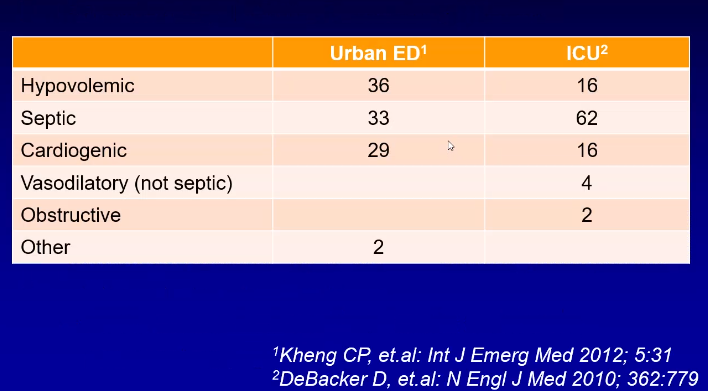

Etiology of Shock

Physiologic Approach

If the blood pressure is low. Either the systemic vascular resistance is low, or the cardiac output is low.

-

Is cardiac output low?

-

If no, vasodilatory shock

-

-

If yes, is the heart empty?

-

If yes, hypovolemic shock

-

If no, there is pump dysfunction

-

LV, RV, valve, pericardium, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism

-

-

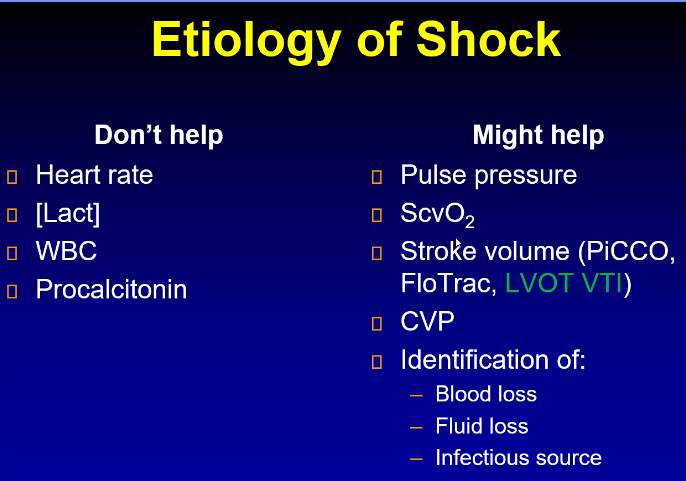

IS CARDIAC OUTPUT LOW?

This question is equivalent to asking if the pulse pressure is low.

Pulse pressure is an indicator for stroke volume as the only other variable is aortic compliance which does not change on a day to day, minute to minute basis.

We have a lot of tools to determine if cardiac output is low, demonstrated above. If cardiac output is not determined to be low, then we are dealing with vasodilatory shock. If it is low, then we need to start working on the differential diagnosis for low cardiac output shock such as hemorrhagic, hypovolemic, cardiogenic (LV, RV, pericardia, Valve, PE)

VASODILATORY SHOCK

Most of the time it is septic shock, but there is a differential including liver failure, vasodilatory drugs, adrenal insufficiency, pancreatitis, paost-cardiac arrest, post-op vasoplegia, thiamine deficiency. This is a state of systemic inflammation or systemic injury.

Remember that most commonly vasodilatory shock is septic, and the most important factor in determining outcome is time to antibiotics. You do not want to miss something like thiamine deficiency because the treatment is very benign. Remember to check their medication list or see the anesthesia operative report as many medications can cause systemic vasodilation.

WHAT IF THE CARDIAC OUTPUT IS LOW?

FLUIDS:

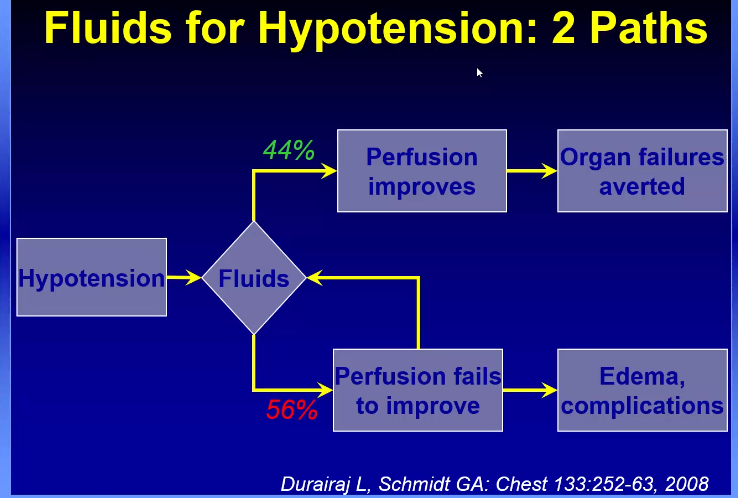

We used to think that anyone is low they need a bolus. Many patients with hypotension and oliguria

The question of fluids versus early vasoactive medications is still yet to be determined. The goal is determine those patients that would benefit from fluid by using pulse pressure variability, passive leg raise, IVC change and avoid giving fluids to those patients that may cause harm.

Bryne et all AJRCCM 2018 demonstrated that in an animal model (septic sheep), fluids versus early vasoactive approach, the fluid arm required more norepinephrine and vasopressin doses over time with higher lactate levels compared to the early vasoactive medication arm.

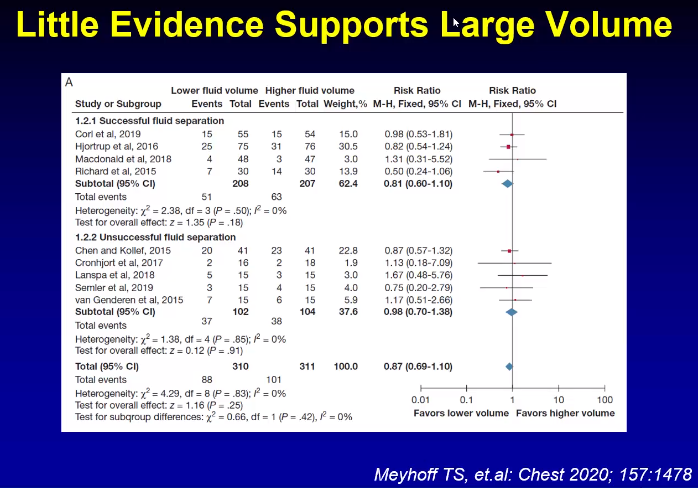

There is little evidence to support large volume of fluids.

There is no harm that has been demonstrated from an early vasoactive approach

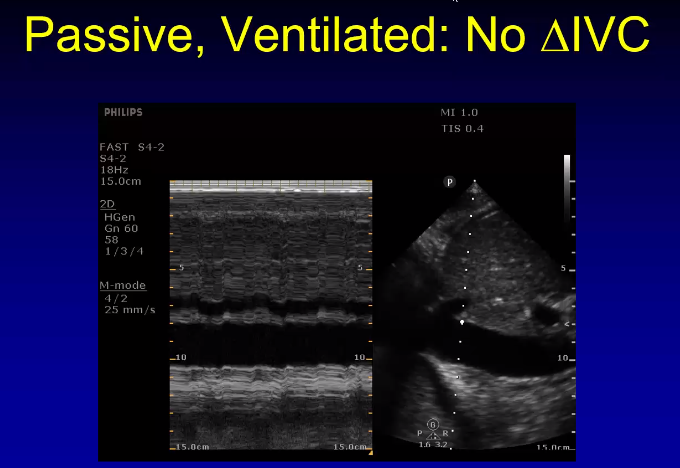

If the patient is spontaneously breathing, there are many more factors that affect IVC collapse and this measurement should be used cautiously to determine fluid responsiveness as it has not been validated in studies.

Then There’s Pump Dysfunction

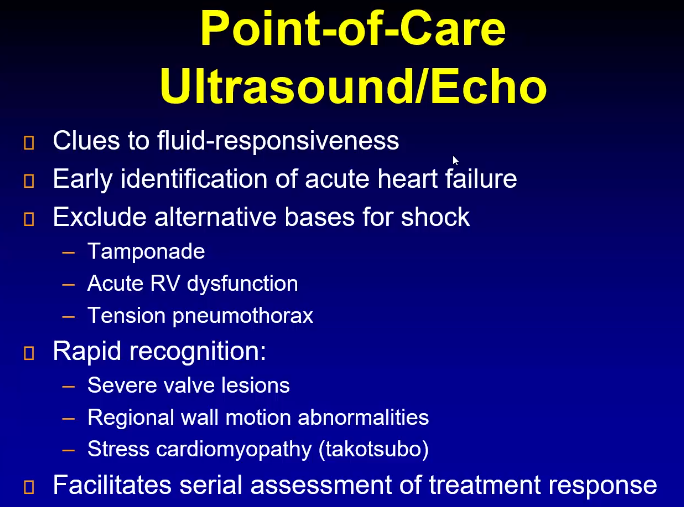

Pump Dysfucntion (complex, but can all be visualized with ECHO)

-

LV dysfunction

-

systolic

-

Diastolic

-

-

RV dysfunction

-

Tamponade

-

Severe valve

-

facility with color doppler.

-

Attempt a Specific Diagnosis as it will affect outcomes

Cardiogenic Shock due to MI: early revascularization will save lives.

PE shock: thrombolysis

Tamponade: pericardiostomy

Flail mitral valve: valve surgery

Tenstion ptx: Chest tube

Shoshin beriber: thiamine

VasoRx

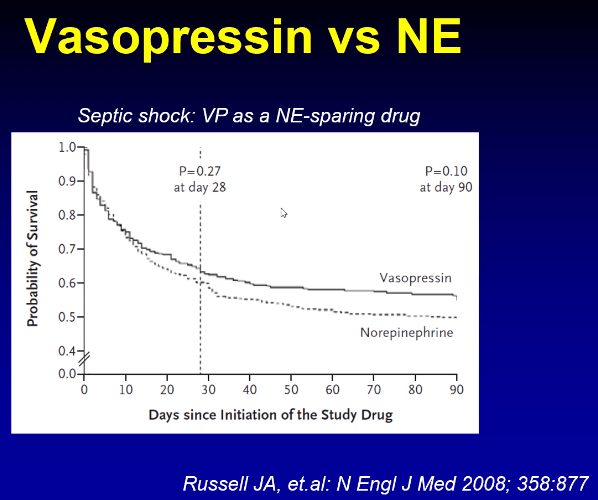

Norepnephrine has been shown to be our first line agent in all forms of shock:

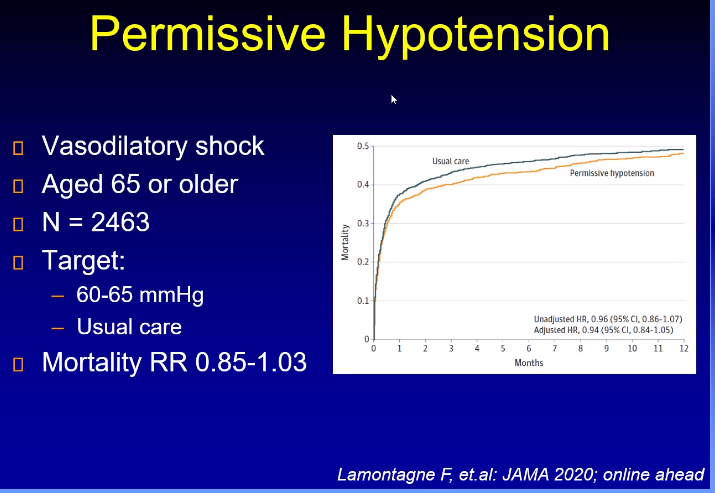

MAP Target 60-65 mm Hg

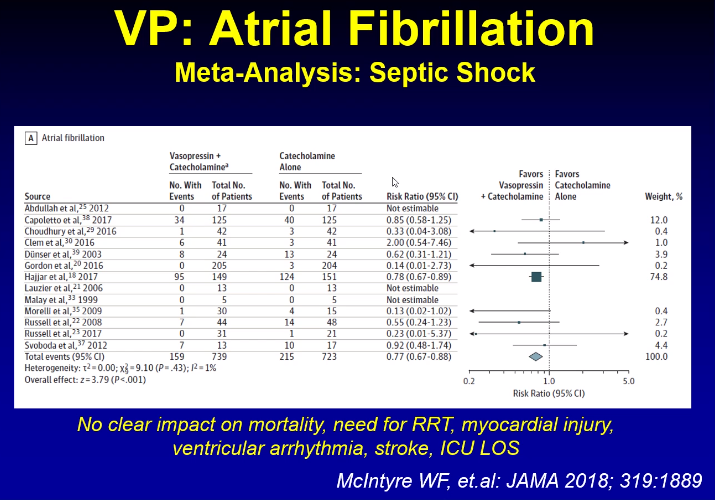

Higher targets have been tested in numerous trials showing no benefit. Higher targets may have some adverse effects such as atrial fibrillation.

Negative trial, outcomes were not improved, but there was no difference between the two arms of 60 and 65 in older patients.

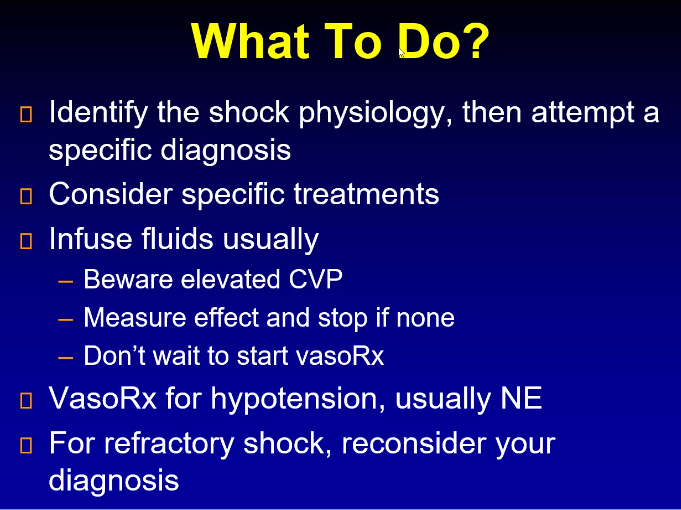

Key Points

-

Shock is classified into three types: (1) hypovolemic (due to inadequate perfusion in the setting of decreased blood volume), (2) cardiogenic (due to poor perfusion from decreased cardiac function), and (3) distributive (due to loss of vascular tone).

-

The basic goals of management in shock, regardless of its type, are to restore perfusion as quickly as possible and to reverse the disease process leading to the shock state.

-

The mainstays of shock treatment include fluid administration, vasopressors, inotropes, and blood transfusion; however, diagnosing and reversing the underlying cause of shock is as important as restoring perfusion.

Additional Resources:

NEJM 360 – Sepsis/Shock

GUIDELINES

Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016

Rhodes A et al. Intens Care Med 2017.

The most recent version of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of sepsis.

Watch this video to see the updates from the 2012 to 2016 guidelines.

The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3)

Singer M et al. JAMA 2016.

Updated definitions and clinical criteria for sepsis and septic shock by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine

LANDMARK TRIALS SHOCK

-

ADRENAL (2018): Hydrocortisone in septic shock

-

Annane Trial (2002): Corticosteroids in septic shock

-

ATHOS-3 (2017): Angiotensin II vs. placebo in vasodilatory shock

-

CORTICUS (2008): Hydrocortisone in septic shock

-

CRISTAL (2013): Colloids vs. crystalloids in shock

-

FEAST (2011): Fluid resuscitation in Sub-Saharan Africa

-

Hydrocortisone, Vitamin C, and Thiamine in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock (2017): Hydrocortisone, Vit C, and thiamine in sepsis

-

IABP-SHOCK II (2012): IABP in MI and cardiogenic shock

-

ProMISe (2015): Multicenter EGDT trial in severe sepsis

-

PROWESS (2001): Activated protein C in severe sepsis

-

PROWESS-SHOCK (2012): Activated protein C in septic shock

-

Rivers Trial (2001): Early goal-directed therapy in sepsis

-

SEPSISPAM (2014): MAP 65-70 vs. 80-85 mmHg in sepsis

-

SHOCK (1999): Early PCI/CABG in MI + shock

-

SOAP II (2010): Dopamine vs. norepinephrine in shock

-

TRISS (2014): Transfusion thresholds in sepsis

-

VASST (2008): Vasopressin in septic shock

INTRODUCTION TO SHOCK LECTURE

Rolando Sanchez, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor

Pulmonary – Critical Care Medicine

July 2018

MANAGING SHOCK

Rolando Sanchez, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor

Pulmonary – Critical Care Medicine

Post by Roger D. Struble MD MPH

July 14 2020